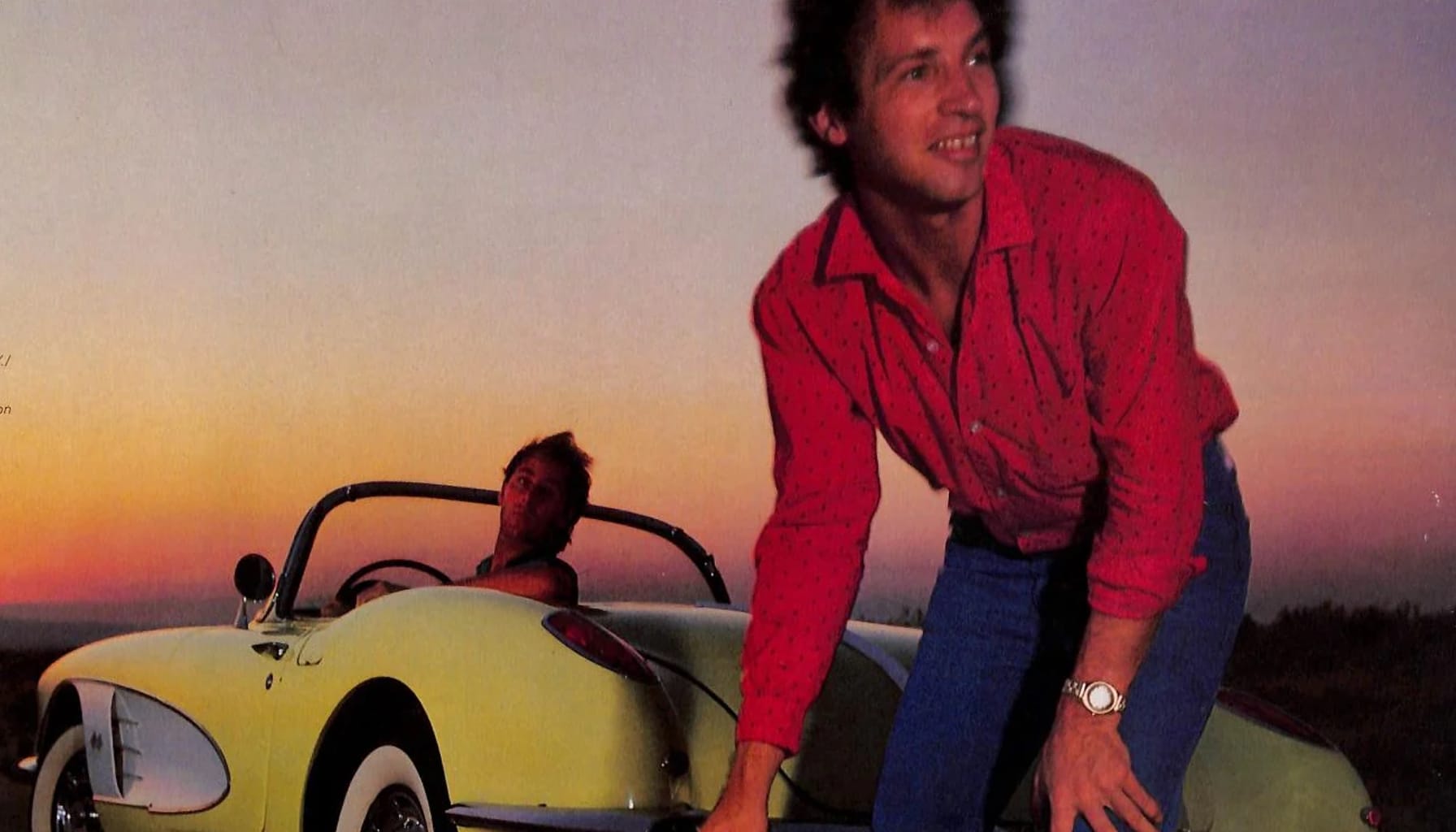

The One After the One-Hit Wonder: Tommy Tutone, "Which Man Are You"

Top 40 success can be so fleeting. Just ask these guys

One-hit wonders have existed as long as we've had hits, so at this point, the list of artists who've boomeranged in and out of the Top 40 is extremely long, containing a million stories and spanning pretty much any genre you could think of. Fundamentally, however, there are really just two types of one-hit wonder acts: Ones that almost notched another hit, usually while their big one was still working its way out of heavy rotation, and ones that just absolutely tanked with their follow-up single and never came close to regaining momentum.

Tommy Tutone falls on the latter end of that spectrum.

(Before we go further, I have to point out that technically, Tommy Tutone isn't a one-hit wonder — before going all the way to No. 4 with "867-5309/Jenny" in 1981, they had a No. 38 single with "Angel Say No," released the previous year. This is one case, though, where I'd argue the big hit so thoroughly overshadowed its predecessor that it almost doesn't exist. This isn't a "Sun Always Shines on TV" situation. Okay, moving on.)

Formed in the late '70s around the creative nucleus of guitarist Jim Keller and frontman/multi-instrumentalist Tommy Heath, Tommy Tutone existed in more or less the same sonic bandwidth occupied by groups like Huey Lewis and the News — they were a little bit rock, a little bit pop, a little bit New Wave, et cetera, depending on what the occasion called for. Lewis is a decent reference point for a number of reasons, really; like him, Heath and Keller were Bay Area guys, and Keller co-wrote "867-5309/Jenny" with Alex Call, who was in Clover with Lewis and helped pen many of his hits with the News.

The point is, Tommy Tutone weren't doing anything exotic with their sound; if anything, they were a solid early '80s example of the type of triangulating that helped a lot of acts keep one foot on the Hot 100 and the other on AOR charts. It made perfect sense that they'd land a record deal with Columbia, and "Angel Say No" must have sounded like the first baby step in a career that was fated to have a few of them before their first big hit finally popped off.

Again, I want to stress just how smoothly commercial Tommy Tutone's sound was in the context of the early '80s. Listen to it from slightly different angles, and you can hear a little early Elvis Costello, a little Glass Houses-era Billy Joel, a little Graham Parker, a little... well, you get the idea. Bottom line, this band was an easy layup for the promo guys at Columbia. Sure, they had a dumb name, but that's never stopped anybody; just ask the Goo Goo Dolls.

Striking while the iron was medium hot, Tommy Tutone followed 1980's Tommy Tutone with 1981's Tommy Tutone 2. Keller initially didn't think much of "867-5309/Jenny," at least not until it started paying his bills; as he later told the Lexington Herald, "When we write a song, we'll play it for friends, managers... if people scream, we do it. If no one says anything, I don't push it. This one was kind of in the middle."

(Keller might have felt that way because Call's the one who came up with the song's nagging riff, which was married to lyrics Keller came up with about a girl whose number he really did see on a bathroom wall. The fact that Call never caught on as a recording artist in his own right seems like a cruel twist of fate that's worth investigating, ideally while listening to some of his solo albums.)

We all know what happened next. Not only was "867-5309/Jenny" a huge hit during its initial chart run, it ended up becoming the type of song that hangs around forever — you'll find it on compilations of '80s hits, you've heard it in commercials, a future version of Tommy Tutone recorded a Christmas version... again, you get the idea. This is one of those songs that generates mailbox money for the people who wrote it long after every echo of it has faded from the Top 40.

The song was also a slow riser. Released to radio in late 1981, it didn't peak until the spring of 1982, which might actually have something to do with what ended up happening to Tommy Tutone next. I don't have easy access to airplay counts, but the Billboard archives tell us that as of mid-June, "867-5309/Jenny" was still in the Top 20, and a month later, it was still on the Hot 100. This was a single with real staying power, in other words; even in an era when it wasn't unusual for a song to take its time reaching its eventual peak, Tommy Tutone's biggest hit reverberated across the airwaves for a very long time.

Perhaps, then, it's understandable that when it came time to deliver a follow-up, nobody wanted to hear it.

Again, it gets a little messy talking about this stuff so many years after the fact, because I'm not sure it would even be possible to unpack the number of spins any given single racked up while it unfurled the long tail of its post-peak Hot 100 run during this era. There were certainly singles that popped hard and sank like a stone back then, but it was also a lot more common for songs to latch onto airplay like a tick and refuse to let go, to the extent that the audience was sick and tired of their general deal when the next single got shipped. I tend to think that's probably what happened to Tommy Tutone.

Additionally, I also tend to think that the follow-up single was a poor choice.

"Which Man Are You" isn't the worst single pick a person could think of, which is to say it's a good deal more radio-friendly than "Cleopatra's Cat." On the other hand, in the context of songs a label might potentially consider worthy of jockeying for Top 40 position in 1982, this is an extremely undistinguished two minutes and 50 seconds. Because everything Tommy Tutone released after "867-5309/Jenny" shit the bed, I assumed they were a band that only had one single to offer, but now that I've given Tommy Tutone 2 a couple of spins, I'm ready to enthusiastically admit that this was an uncharitable assumption; in reality, the suits at Columbia really did have better options to choose from.

Here's where I say one more time that it's entirely possible that Tommy Tutone were so thoroughly burned at radio after "867-5309/Jenny" that it made absolutely no difference which song was picked as the follow-up single. It's perhaps entirely likely that even the catchiest single in the world would have flopped. But it's also reasonable to assume that the guys at Columbia Records didn't see things this way; instead, they were likely looking to add a couple hundred thousand records to Tommy Tutone 2's sales tally.

Hindsight is 20/20, but I can't pretend I don't have the benefit of it, and therefore I don't feel bad about saying "Baby It's Alright" would have been a better bet. "Only One" might have worked, too. In a different world, I feel like those two tracks — in either order — could have extended Tommy Tutone's hitmaking streak. Unfortunately for Heath and Keller's royalty statements, we do not live in this world; instead, "Which Man Are You" failed to chart, setting the stage for the masterclass in whiffery that occurred when the band returned in 1983 with their third LP, National Emotion.

Tommy Tutone peaked at No. 68; Tommy Tutone 2 topped out at No. 20; National Emotion ended its brief chart run at a startling No. 179. In a 1990 interview, Heath argued that Emotion's failure could be blamed on the notion that "People in the record business wanted to categorize us and we couldn't be pinned down to one thing," but that's the type of quote you read from artists who absolutely can be pinned down to one thing. Having listened to the album, I'd argue that it makes a lot more sense to say the band spent a year coming up with a record full of middling material that tended to flash a troublingly misogynistic streak; it also didn't help that — as Heath put it in 1986 — "I went to work one day and all the people who'd made me famous had been fired."

As far as the charts were concerned, that's where things ended for Tommy Tutone, although like basically every other band that became a brand, they've persisted more or less continually since their brush with fame. Their Wikipedia page says they broke up in 1984 and reunited in 1996, but this is a lie; the 1986 and 1990 interviews I referenced in the previous paragraph were both conducted during Tommy Tutone tours. As near as I can tell, Heath has never really stopped booking dates with whatever Tommy Tutone lineup happens to be near at hand, all while continuing to release albums every so often, and I say good for him — although I haven't actually heard any of his post-National Emotion work, the stuff I have heard makes a solid case for the guy as a decently talented songwriter and charismatic-enough frontman.

At this point in the rock 'n' roll sweepstakes, pretty much everybody who strapped on a guitar wanted to sell a million records and hit the top of the charts. Some acts, though, weren't really built for that type of success; instead, they were better served by building local audiences, touring to smaller but more passionate crowds, and maybe knocking out a medium-sized hit if they really got lucky. Occasionally, this type of act could break big and benefit from it — Huey Lewis and the News are a prime example — but more often than not, all that attention and undue pressure had a way of warping their artistic output, if not their legacy.

To put it another way: I said earlier that Tommy Tutone isn't technically a one-hit wonder, but I suppose I'd also argue that they aren't spiritually one either. Rather than MTV darlings, they were meant to be road dogs — the type of group that opens for Quarterflash and slays the crowd, building a reputation one show at a time. Listen to Tommy Tutone 2 without reliving "867-5309/Jenny" one more goddamn time and see if you don't agree.